I never before knew pain; Now I till a field seeded with sorrow.

Anonymous

In circumstances where young girls are forcibly married to much older men; where honor killings survive into present day; where the price women pay for finding love outside marriage is to be stoned to death – a tradition survives alongside of rebellion through poetry, of women speaking boldly about their lives and hopes, dreams and desires.

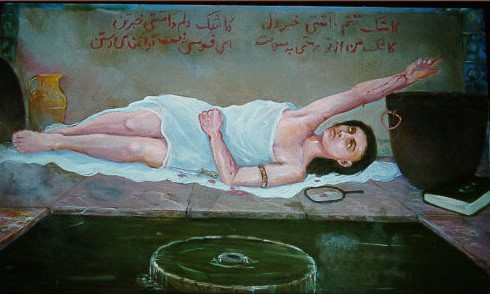

A revered art form in Afghani culture, the tradition of expressing thought through poetry goes back thousands of years. Although much of what survives from the past was written by men, some of the most powerful verses to survive into present day include those Rabia Balki – the 10th Century court poet (and now a symbol of education and empowerment for women) who wanted to marry for love and died writing poems in her own blood when forbidden.

But the roots of poetry in Afghanistan spread much further than what was written in courts, and of particular fascination to me are landays, a form of oral poetry from the Pashtun culture. Built in couplets, these short fragments have been passed down over the years through rural mountain communities. Over time, words have changed, fragments been replaced, images morphed into things recognizable in contemporary culture. But the core of the poetry remains the same – they tell stories of war and separation, grief and love, self and home. And it is primarily a women’s form of poetry; when the poems speak of love, they distinguish between the husband a girl is forced to marry and the lover she chooses; they speak of the grief felt by mothers and daughters; the speak of war in the voices of those left behind.

My beloved sacrificed himself for our country, I sew his shroud with my hair.

Anonymous

In 22 short syllables, two rhyming lines, you find the raw stories of women’s lives.

I bend towards you with my body, like a vine twisting along the earth.

Anonymous

One of my current projects is a song commission from Songfest, and I remember that the earliest conversations I had with the artistic director and with soprano Martha Guth were right around the time that the US was pulling out of Afghanistan. And I remember wondering – as many did – what that would mean for the people left behind. During the Taliban’s regime, music of many sorts had been banned, girls had been forced out of schools and higher education, women who had built themselves careers during more liberal times were forced out of work and abruptly back behind closed doors. And yet – the fighting spirit and sense of rebellion being so deeply engrained into the culture – women still fought to make their voices heard in whatever ways they could. And yet I wondered in reading the news how quickly we, outside the country, might forget the people left to pick up the pieces ….The mountains of Afghanistan feel like a world away, well out of sight, and too easy to fall out of mind. For this project, I wanted to keep the voices of those women front and center.

Most of the credit in collecting landays goes to two individuals – Sayd Majrouh, who spent years in the mountains collecting landays before he was assassinated by what would become the Taliban; and Eliza Griswold, who took up where his work left off, revisiting Afghanistan in the 1990s onwards to gather and share women’s stories.

For an oral art form from a remote part of the world frequently under violent conflict, what’s available in any recorded format is necessarily limited, but in searching across published articles, books, and online poetry groups in many languages, one can start to get a sense of the poems, both the traditional and the contemporary. Below is a collection of landays I found in researching for this project. They are anonymous, although the translations from Pashto, Arabic, Spanish, French and Portuguese have been made by various translators including myself.

A selection of landays became the texts for my song cycle commissioned by Songfest with support from the Sorel Foundation.

Other vocal works of mine inspired by women’s stories include Waves of Change and Enchantress of Numbers.

Links to more information about Afghan women’s poetry and landays:

Stephanie Sinclair’s work photographing and documenting child marriage in Afghanistan

More on Seamus Murphy and Eliza Griswold’s work documenting Landays